In this blog post I would like to touch on the topic of resource management for Docker containers. It is often unclear how it works and what we can and cannot do. I hope that after reading this blog post resource management will be a bit easier for you to understand.

|

Note

|

I assume that you are running Docker on a systemd enabled operating system. If you are on RHEL/CentOS 7+ or Fedora 19+ this is certainly true. But please note that there can be some changes in the available configuration options between different systemd versions. When in doubt, use the systemd man pages for the system you work with. |

The basics

Docker uses cgroups to group processes running in the container. This allows you to manage the resources of a group of processes, which is very valuable, as you can imagine.

If we run an operating system which uses

systemd as the service

manager, every process (not only the ones inside of the container) will be placed in

a cgroups tree. You can see it for yourself if you run the systemd-cgls command:

$ systemd-cgls ├─1 /usr/lib/systemd/systemd --switched-root --system --deserialize 22 ├─machine.slice │ └─machine-qemu\x2drhel7.scope │ └─29898 /usr/bin/qemu-system-x86_64 -machine accel=kvm -name rhel7 -S -machine pc-i440fx-1.6,accel=kvm,usb=off -cpu SandyBridge -m 2048 ├─system.slice │ ├─avahi-daemon.service │ │ ├─ 905 avahi-daemon: running [mistress.local │ │ └─1055 avahi-daemon: chroot helpe │ ├─dbus.service │ │ └─890 /bin/dbus-daemon --system --address=systemd: --nofork --nopidfile --systemd-activation │ ├─firewalld.service │ │ └─887 /usr/bin/python -Es /usr/sbin/firewalld --nofork --nopid │ ├─lvm2-lvmetad.service │ │ └─512 /usr/sbin/lvmetad -f │ ├─abrtd.service │ │ └─909 /usr/sbin/abrtd -d -s │ ├─wpa_supplicant.service │ │ └─1289 /usr/sbin/wpa_supplicant -u -f /var/log/wpa_supplicant.log -c /etc/wpa_supplicant/wpa_supplicant.conf -u -f /var/log/wpa_supplica │ ├─systemd-machined.service │ │ └─29899 /usr/lib/systemd/systemd-machined [SNIP]

This approach gives a lot of flexibility when we want to manage resources, since we can manage every group individually. Although this blog post focuses on containers, the same principle applies to other processes as well.

|

Note

|

If you want to read more about resource management with systemd I highly recommend the Resource Management and Linux Containers Guide for RHEL 7. |

A note on testing

In my examples I’ll use the stress tool that helps me to generate some load

in the containers so I can actually see the resource limits being applied. I

created a custom Docker images called (surprisingly) stress using this Dockerfile:

FROM fedora:latest

RUN yum -y install stress && yum clean all

ENTRYPOINT ["stress"]A note on resource reporting tools

The tools you are used to using to report usage like top, /proc/meminfo and

so on are not cgroups aware. This means that they’ll report the information

about the host even if we run them inside of a container. I found a

nice blog

post from Fabio Kung on this topic. Give it a read.

So, what can we do?

If you want to quickly find which container (or any systemd service, really) uses the most resources

on the host I recommend the systemd-cgtop command:

$ systemd-cgtop Path Tasks %CPU Memory Input/s Output/s / 226 13.0 6.7G - - /system.slice 47 2.2 16.0M - - /system.slice/gdm.service 2 2.1 - - - /system.slice/rngd.service 1 0.0 - - - /system.slice/NetworkManager.service 2 - - - - [SNIP]

This tool can give you a quick overview of what’s going on on the system right

now. But if you want to get some detailed information about the usage (for

example you need to create nice graphs) you will want to parse the

/sys/fs/cgroup/… directories. I’ll show you where to find useful files for each

resource I will talk about (look at the CGroups fs paragraphs below).

CPU

Docker makes it possible (via the -c

switch

of the run command) to specify a value of shares of the CPU available to the

container. This is a relative weight and has nothing to do with the actual

processor speed. In fact, there is no way to say that a container should have

access only to 1Ghz of the CPU. Keep that in mind.

Every new container will have 1024 shares of CPU by default. This value does

not mean anything, when speaking of it alone. But if we start two containers

and both will use 100% CPU, the CPU time will be divided equally between the two

containers because they both have the same CPU shares (for the sake of

simplicity I assume that there are no other processes running).

If we set one container’s CPU shares to 512 it will receive half of the CPU

time compared to the other container. But this does not mean that it can use

only half of the CPU. If the other container (with 1024 shares) is idle — our container will be allowed to use 100% of the CPU. That’s another thing to note.

Limits are enforced only when they should be. CGroups does not limit the processes upfront (for example by not allowing them to run fast, even if there are free resources). Instead it gives as much as it can and limits only when necessary (for example when many processes start to use the CPU heavily at the same time).

Of course it’s not easy (and I would say impossible) to say how many resources will be assigned to your process. It really depends on how other processes will behave and how many shares are assigned to them.

Example: managing the CPU shares of a container

As I mentioned before you can use the -c switch to manage the value of shares

assigned to all processes running inside of a Docker container.

Since I have 4 cores on my machine available, I’ll tell stress to use all 4:

$ docker run -it --rm stress --cpu 4 stress: info: [1] dispatching hogs: 4 cpu, 0 io, 0 vm, 0 hdd

If we start two containers the same way, both will use around 50% of the CPU. But what happens if we modify the CPU shares for one container?

$ docker run -it --rm -c 512 stress --cpu 4 stress: info: [1] dispatching hogs: 4 cpu, 0 io, 0 vm, 0 hdd

As you can see, the CPU is divided between the two containers in such a way that the first container uses ~60% of the CPU and the other ~30%. This seems to be the expected result.

|

Note

|

The missing ~10% of the CPU was taken by GNOME, Chrome and my music player, in case you were wondering. |

Attaching containers to cores

Besides limiting shares of the CPU, we can do one more thing: we can pin the container’s processes to a particular processor (core).

To do this, we use the --cpuset switch of the docker run command.

To allow execution only on the first core:

docker run -it --rm --cpuset=0 stress --cpu 1

To allow execution only on the first two cores:

docker run -it --rm --cpuset=0,1 stress --cpu 2

You can of course mix the option --cpuset with -c.

|

Note

|

Share enforcement will only take place when the processes are run on the same core. This means that if you pin one container to the first core and the other container to the second core, both will use 100% of each core, even if they have different a CPU share value set (once again, I assume that only these two containers are running on the host). |

Changing the shares value for a running container

It is possible to change the value of shares for a running container (or any other process, of course). You can directly interact with the cgroups filesystem, but since we have systemd we can leverage it to manage this for us (since it manages the processes anyhow).

For this purpose we’ll use the systemctl command with the set-property

argument. Every new container created using the docker run command will have

a systemd scope automatically assigned under which all of its processes will be

executed. To change the CPU share for all processes in the container we just

need to change it for the scope, like so:

$ sudo systemctl set-property docker-4be96b853089bc6044b29cb873cac460b429cfcbdd0e877c0868eb2a901dbf80.scope CPUShares=512

|

Note

|

Add --runtime to change the setting temporarily. Otherwise, this setting will be remembered when the host is restarted.

|

This changes the default value from 1024 to 512. You can see the result

below. The change happens somewhere in the middle of the recording. Please note

the CPU usage. In systemd-cgtop 100% means full use of 1 core and this is

correct since I bound both containers to the same core.

|

Note

|

To show all properties you can use the systemctl show docker-4be96b853089bc6044b29cb873cac460b429cfcbdd0e877c0868eb2a901dbf80.scope command. To list all available properties take a look at man systemd.resource-control.

|

CGroups fs

You can find all the information about the CPU for a specific container under

/sys/fs/cgroup/cpu/system.slice/docker-$FULL_CONTAINER_ID.scope/, for example:

$ ls /sys/fs/cgroup/cpu/system.slice/docker-6935854d444d78abe52d629cb9d680334751a0cda82e11d2610e041d77a62b3f.scope/ cgroup.clone_children cpuacct.usage_percpu cpu.rt_runtime_us tasks cgroup.procs cpu.cfs_period_us cpu.shares cpuacct.stat cpu.cfs_quota_us cpu.stat cpuacct.usage cpu.rt_period_us notify_on_release

|

Note

|

More information about these files can be found in the RHEL Resource Management Guide. This information is spread across the cpu, cpuacct and cpuset sections. |

Recap

A few things to remember:

-

a CPU share is just a number — it’s not related to the CPU speed

-

By default new containers have

1024shares -

On an idle host a container with low shares will still be able to use 100% of the CPU

-

You can pin a container to specific core, if you want

Memory

Now let’s take a look at limiting memory.

The first thing to note is that a container can use all of the memory on the host with the default settings.

If you want to limit memory for all of the processes inside of the container just

use the -m docker run switch. You can define the value in bytes or by adding

a suffix (k, m or g).

Example: managing the memory shares of a container

You can use the -m switch like so:

$ docker run -it --rm -m 128m fedora bash

To show that the limitation actually works I’ll use my stress image again. Consider the following run:

$ docker run -it --rm -m 128m stress --vm 1 --vm-bytes 128M --vm-hang 0 stress: info: [1] dispatching hogs: 0 cpu, 0 io, 1 vm, 0 hdd

The stress tool will create one process and try to allocate 128MB of memory to it. It works fine, good. But what happens if we try to use more than we have actually allocated for the container?

$ docker run -it --rm -m 128m stress --vm 1 --vm-bytes 200M --vm-hang 0 stress: info: [1] dispatching hogs: 0 cpu, 0 io, 1 vm, 0 hdd

It works too. Surprising? Yes I agree.

We can find the explanation for this in the

libcontainer

source code (Docker’s interface to cgroups). We can see there that by default

the memory.memsw.limit_in_bytes value is set to twice as much as the memory

parameter we specify while starting a container. What does the

memory.memsw.limit_in_bytes parameter say? It is a

sum

of memory and swap. This means that Docker will assign to the container -m

amount of memory as well as -m amount of swap.

The current Docker interface does not allow us to specify how much (or disable it entirely) swap should be allowed, so we need live with it for now.

With the above information we can run our example again. This time we will try to allocate over twice the amount of memory we assign. This should use all of the memory and all of the swap, then die.

$ docker run -it --rm -m 128m stress --vm 1 --vm-bytes 260M --vm-hang 0 stress: info: [1] dispatching hogs: 0 cpu, 0 io, 1 vm, 0 hdd stress: FAIL: [1] (415) <-- worker 6 got signal 9 stress: WARN: [1] (417) now reaping child worker processes stress: FAIL: [1] (421) kill error: No such process stress: FAIL: [1] (451) failed run completed in 5s

If you try once again to allocate for example 250MB (--vm-bytes

250M) it will work just fine.

|

Warning

|

If we don’t limit the memory by using -m switch the swap size will be unlimited too.

[1]

|

Having no limit on memory can lead to issues where one container can easily

make the whole system unstable and as a result unusable. So please remember:

always use the -m parameter [2].

CGroups fs

You can find all the information about the memory under

/sys/fs/cgroup/memory/system.slice/docker-$FULL_CONTAINER_ID.scope/, for example:

$ ls /sys/fs/cgroup/memory/system.slice/docker-48db72d492307799d8b3e37a48627af464d19895601f18a82702116b097e8396.scope/ cgroup.clone_children memory.memsw.failcnt cgroup.event_control memory.memsw.limit_in_bytes cgroup.procs memory.memsw.max_usage_in_bytes memory.failcnt memory.memsw.usage_in_bytes memory.force_empty memory.move_charge_at_immigrate memory.kmem.failcnt memory.numa_stat memory.kmem.limit_in_bytes memory.oom_control memory.kmem.max_usage_in_bytes memory.pressure_level memory.kmem.slabinfo memory.soft_limit_in_bytes memory.kmem.tcp.failcnt memory.stat memory.kmem.tcp.limit_in_bytes memory.swappiness memory.kmem.tcp.max_usage_in_bytes memory.usage_in_bytes memory.kmem.tcp.usage_in_bytes memory.use_hierarchy memory.kmem.usage_in_bytes notify_on_release memory.limit_in_bytes tasks memory.max_usage_in_bytes

|

Note

|

More information about these files can be found in the RHEL Resource Management Guide, memory section. |

Block devices (disk)

With block devices we can think about two different types of limits:

-

Read/write speed

-

Amount of space available to write (quota)

The first one is pretty easy to enforce, whereas the second is still unsolved.

|

Note

|

I assume you are using the devicemapper storage backed for Docker. Everything below may be untrue for other backends. |

Limiting read/write speed

Docker does not provide any switch that can be used to define how fast we can

read or write data to a block device. But CGroups does have it built-in. And

it’s even exposed in systemd via the BlockIO* properties.

To limit read and write speed we can use the BlockIOReadBandwidth and

BlockIOWriteBandwidth properties, respectively.

By default the bandwith is not limited. This means that one container can make the disk hot, especially if it starts to swap…

Example: limiting write speed

Let’s measure the speed with no limits enforced:

$ docker run -it --rm --name block-device-test fedora bash bash-4.2# time $(dd if=/dev/zero of=testfile0 bs=1000 count=100000 && sync) 100000+0 records in 100000+0 records out 100000000 bytes (100 MB) copied, 0.202718 s, 493 MB/s real 0m3.838s user 0m0.018s sys 0m0.213s

It took 3.8 sec to write 100MB of data which gives us about 26MB/s. Let’s try to limit the disk speed a bit.

To be able to adjust the bandwitch available for the container we need to know

exactly where the container filesystem is mounted. You can find it when you

execute the mount command from inside of the container and find the device that

is mounted on the root filesystem:

$ mount /dev/mapper/docker-253:0-3408580-d2115072c442b0453b3df3b16e8366ac9fd3defd4cecd182317a6f195dab3b88 on / type ext4 (rw,relatime,context="system_u:object_r:svirt_sandbox_file_t:s0:c447,c990",discard,stripe=16,data=ordered) proc on /proc type proc (rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime) tmpfs on /dev type tmpfs (rw,nosuid,context="system_u:object_r:svirt_sandbox_file_t:s0:c447,c990",mode=755) [SNIP]

In our case this is /dev/mapper/docker-253:0-3408580-d2115072c442b0453b3df3b16e8366ac9fd3defd4cecd182317a6f195dab3b88.

You can also use the nsenter command to get this value, like so:

$ sudo /usr/bin/nsenter --target $(docker inspect -f '{{ .State.Pid }}' $CONTAINER_ID) --mount --uts --ipc --net --pid mount | head -1 | awk '{ print $1 }'

/dev/mapper/docker-253:0-3408580-d2115072c442b0453b3df3b16e8366ac9fd3defd4cecd182317a6f195dab3b88

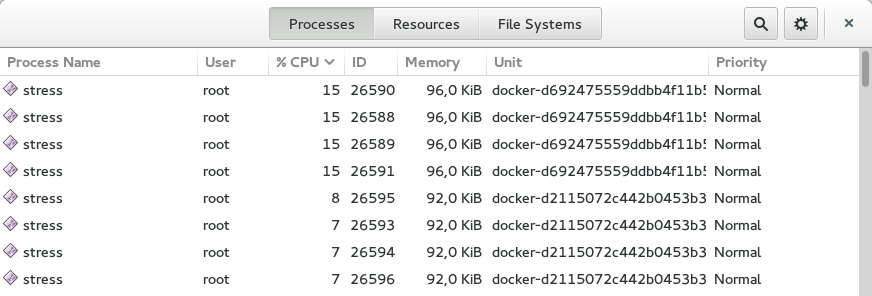

Now we can change the value of the BlockIOWriteBandwidth property, like so:

$ sudo systemctl set-property --runtime docker-d2115072c442b0453b3df3b16e8366ac9fd3defd4cecd182317a6f195dab3b88.scope "BlockIOWriteBandwidth=/dev/mapper/docker-253:0-3408580-d2115072c442b0453b3df3b16e8366ac9fd3defd4cecd182317a6f195dab3b88 10M"

This should limit the disk write speed to 10MB/s, so let’s run dd again:

bash-4.2# time $(dd if=/dev/zero of=testfile0 bs=1000 count=100000 && sync) 100000+0 records in 100000+0 records out 100000000 bytes (100 MB) copied, 0.229776 s, 435 MB/s real 0m10.428s user 0m0.012s sys 0m0.276s

It seems to work, it took 10s to write 100MB to the disk, so the speed was about 10MB/s.

|

Note

|

The same applies to limiting the read bandwith with the difference being you use the

BlockIOReadBandwidth property.

|

Limiting disk space

As I mentioned before this is tough topic. By default you get 10GB of space for each container. Sometimes this is too much, sometimes we cannot fit all of our data there. Unfortunately there is not much we can do about it now.

The only thing we can do is to change the default value for new containers. If you think that some other value (for example 5GB) is a beter fit in your case, you can do it by specifying the --storage-opt for the Docker daemon, like so:

docker -d --storage-opt dm.basesize=5G

You can tweak some other things, but please keep in mind that it requires restarting the Docker daemon afterwards. More info can be found in the readme.

CGroups fs

You can find all the information about the block devices under

/sys/fs/cgroup/blkio/system.slice/docker-$FULL_CONTAINER_ID.scope/, for example:

$ ls /sys/fs/cgroup/blkio/system.slice/docker-48db72d492307799d8b3e37a48627af464d19895601f18a82702116b097e8396.scope/ blkio.io_merged blkio.sectors_recursive blkio.io_merged_recursive blkio.throttle.io_service_bytes blkio.io_queued blkio.throttle.io_serviced blkio.io_queued_recursive blkio.throttle.read_bps_device blkio.io_service_bytes blkio.throttle.read_iops_device blkio.io_service_bytes_recursive blkio.throttle.write_bps_device blkio.io_serviced blkio.throttle.write_iops_device blkio.io_serviced_recursive blkio.time blkio.io_service_time blkio.time_recursive blkio.io_service_time_recursive blkio.weight blkio.io_wait_time blkio.weight_device blkio.io_wait_time_recursive cgroup.clone_children blkio.leaf_weight cgroup.procs blkio.leaf_weight_device notify_on_release blkio.reset_stats tasks blkio.sectors

|

Note

|

More information about these files can be found in the RHEL Resource Management Guide, blkio section. |

Summary

As you can see resource management for Docker containers is possible. It’s even pretty easy. The only thing that bothers me (and others too) is that we cannot set a quota for disk usage. There is an issue filled upstream — watch it and comment.

Hope you found my post useful. Happy dockerizing!